One of the critical (and most overlooked) aspects of compensating founders and early-stage employees is to understand the effect of Section 83(b) of the tax code on taxation of founders’ shares (aka restricted stock).

When you receive stock subject to vesting—or exercise a stock option before it vests (“early-exercise” stock option)—you have 30 days to file a Section 83(b) election with the IRS. This lets you pay income taxes upfront on the difference between the fair market value of the shares at the time you received them and what you paid.

At incorporation, market value usually equals the purchase price (fractions of a cent per share), so the immediate tax cost is minimal.

Filing an 83(b) locks in that low valuation. Future gains are taxed only when you sell, typically at long-term capital gains rates. Without an 83(b), you’ll be taxed at ordinary income rates each time shares vest—often on illiquid stock you can’t sell to cover the tax bill.

Let’s Do the Math

Let’s compare outcomes with and without an 83(b) election, assuming that you are the sole founder buying 8 million shares for $0.00001 and paying $80 total. On a standard vesting schedule, you earn 25% of your stock each year until it’s fully yours.

With an 83(b) Election: About $0 Tax Upfront

If the market value of your stock at purchase is also $0.00001 per share, the IRS sees no gain—so there’s essentially no income tax. By filing 83(b) right away, you lock in today’s low value.

All future growth in the stock price will be taxed only when you eventually sell, at capital gains rates (which can be lower than regular income tax).

Without an 83(b) Election: About $1.85 Million in Taxes

Skip the 83(b), and every time your stock vests the IRS taxes you on the then-current value as regular income.

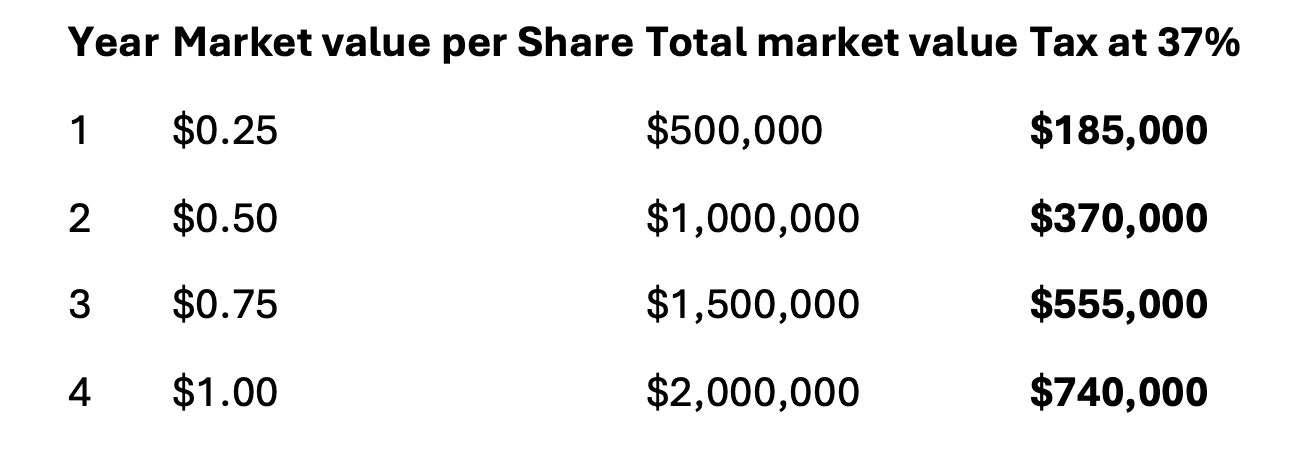

Assume the company grows so that each share is worth $1 after four years (vesting evenly at 2 million shares per year) and you’re in the top 37% bracket:

And remember: these are paper gains.

If your shares are illiquid (can’t easily be sold)—as they often are— you’d still owe the IRS cash you might not have, creating real financial strain.

Unfortunately, if you miss a 30-day window to file an 83(b) election, you can’t file late. However, there are a few strategies that practitioners sometimes use to mitigate the damage. In all of these cases, it’s crucial to obtain a 409A valuation to determine the stock’s market value. You can read more about 409A valuations—and how they can keep you out of serious tax trouble—here.

1. Accelerating Vesting Now and Re-Vesting Later

WHAT: Accelerating vesting removes the “substantial risk of forfeiture” by the Company, so the shares become fully yours right away, instead of gradually over time. When this happens, you have to pay tax immediately based on what the shares are worth today. If the shares are still very cheap or basically worthless, the tax cost will be very small.

WHO: This approach works best for a solo founder when the shares are worth very little: the tax cost is minimal, the Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) clock stays intact, and there’s no risk of co-founder “dead equity” (shares stuck with a departed co-founder). You can read more about what QSBS is and how it might save you millions here.

WHY NOT: Investors do not like accelerating vesting for something that was (in their view) the grantee's fault. A probable solution is to accelerate now but, after a waiting period (e.g., six months or more), put you back on a new vesting schedule. That way, retention incentives are restored while the tax problem has been addressed.

2. Making Shares “Transferable”

WHAT: Another option is to amend your stock purchase agreement so your restricted stock can be transferred (sold or given) to a third party. Once it’s transferable, the IRS treats it as income right away. As in the acceleration scenario, you’ll still owe immediate tax on the difference between what the stock is worth then and what you paid.

WHO: This path is rare and makes sense for founders or top executives with significant leverage.

WHY NOT: This fix is also not without its issues. The amendment is highly technical. The shares must be fully vested before they can be transferred to a third party, a feature investors do not like. There is also very little guidance from the IRS.

3. Cancel and Re-Grant as Stock Options

WHAT: Another path is to cancel the restricted stock and grant a stock option instead, with immediate early exercise and a timely 83(b) election. Because restricted stock and early-exercised options are economically similar, this can produce nearly the same tax result while also giving the company clear repurchase rights.

WHO: This is often more attractive in a multi-founder scenario, where co-founder/investor concerns about “dead equity” are strongest.

WHY NOT: The downsides are that the QSBS clock resets, and the company must carefully document a clear and legitimate business rationale to avoid the IRS viewing the maneuver as a sham transaction.

4. Loan or Bonus

WHAT: Your investors may agree to help cover the tax bill—the company can give you a loan (a real good-faith debt) or pay a discretionary bonus.

WHO: This path usually makes sense for founders who have strong investor support and whose company has enough cash (or investor appetite).

WHY NOT: Loans must be carefully documented to avoid IRS challenges, and they put you personally on the hook for repayment. Bonuses create dilution or strain cash reserves, which other investors may resist. Either way, this option depends heavily on investor cooperation and company finances.

5. Other Options (Not Recommended)

Some founders ask about dissolving the company and reissuing stock in a new entity, or even backdating documents. Neither is advisable. Dissolving and restarting is messy, risks being treated as a sham by the IRS, and can create bigger headaches than it solves. Backdating is outright illegal.

Why does it matter to the Company?

It’s a common misconception that 83(b) elections are purely personal tax filings. While partly true, if you don’t file one, the company must withhold taxes on each vesting date and can face substantial penalties if it doesn’t. That’s why keeping IRS-stamped copies of 83(b) elections on file is essential for the Company’s compliance and ensures a smooth due diligence process during fundraising.

Online Filing for Section 83(b) Elections

Taxpayers can now file Section 83(b) elections online. To do so, they must create an IRS online account, complete Form 15620 directly on the IRS website, and then either submit the form electronically (preferred method) or download and file it by mail.

We caution that the above is a general summary (it does not, for example, address partnership equity incentives or non-US tax implications) and may not address your specific circumstances. It is not individualized tax or legal advice. Always consult the experienced tax and startup lawyers to navigate these complexities, ensure compliance with tax and corporate laws and minimize potential liabilities.